Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

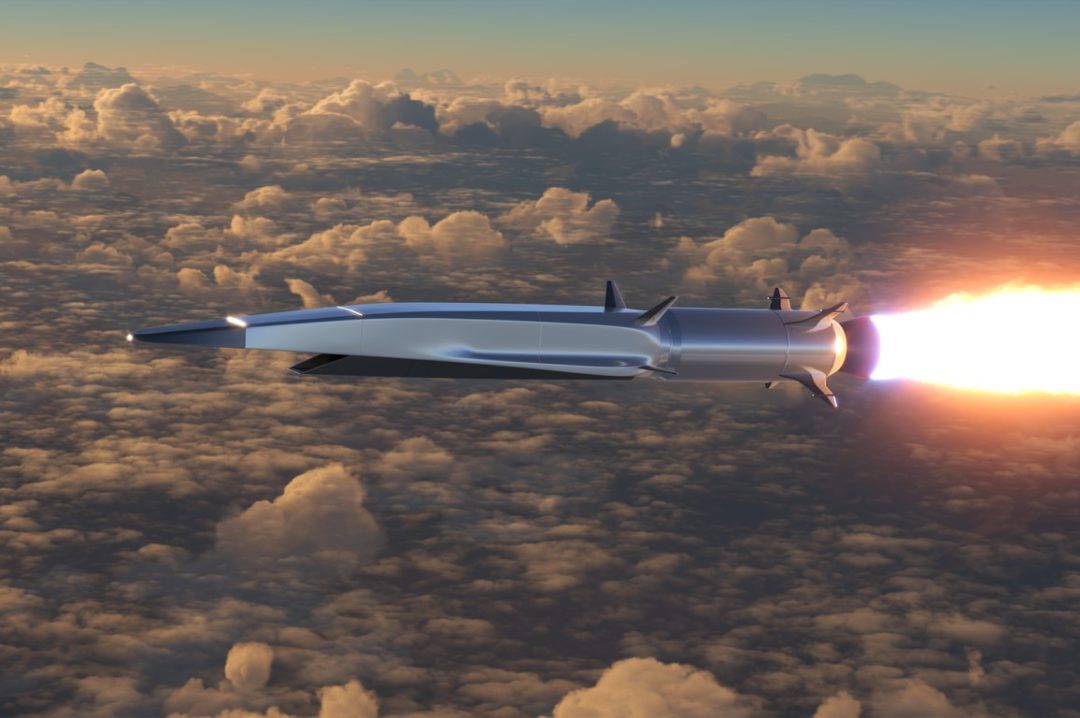

Image: iStock.com/Alexyz3d

The U.S. Department of Defense wants to scale up the production of hypersonic weapons — but the supply chain to make that happen doesn’t exist.

A new report by the National Defense Industrial Association’s Emerging Technologies Institute charges that DOD “has often wavered in its commitment to fielding hypersonic systems at scale. Some years, it has been a clear priority while other times, the commitment has been ambiguous.”

At the heart of DOD’s failure to advance hypersonic weapons development is an inadequate supply chain. ETI says the “manufacturing base, supply of critical materials, testing infrastructure and workforce are incapable of supporting DOD’s ambitious plans.”

Hypersonic weapons travel at least five times the speed of sound, are highly maneuverable, and are capable of avoiding countermeasures like missile defense systems. “They’re fast enough that current jets can’t easily intercept,” says Tim Reed, chief executive officer of Lynx Software Technologies, which sells applications for the aerospace and defense industries.

Reed seconds the conclusions of the ETI report. He says that delays or disruptions in the aerospace and defense supply chain “can upset the production and maintenance of military systems, restricting a country’s ability to quickly respond to national security threats.”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, launching a war that has already lasted more than 500 days, could serve as a wakeup call. “In today’s climate of geopolitical instability, reducing these delays is crucial for the protection of any country,” Reed says.

Development of a supply chain for cutting-edge hypersonic weapons requires a concerted program of research and development by key suppliers and producers. But in the years prior to the advent of the war in Ukraine, Reed believes, “there have been some muscles atrophied in the manufacturing supply base, to be able to produce armaments and tools needed for active combat situations.”

Among the potential weak points is an overreliance on China and Taiwan for critical electronic components. The ability to keep sourcing from those locations is “clearly in doubt,” Reed says.

Even the simplest supply chain consists of multiple independent parts, each critical to the whole. Reed cites “I, Pencil,” an essay published in the December, 1958 issue of the libertarian magazine The Freeman, which describes the complex relationships among suppliers, no one of which possesses all the pieces of the puzzle. And when it comes to production of sophisticated defense systems, it’s often difficult to ensure that each of those providers hails from a country that’s allied with U.S. interests.

Western Europe, Japan and even Taiwan are skilled at high-end design and manufacturing, Reed says. “But one way or another, if you’re buying parts from a particular supplier, they’re probably going to have some reliance [on geopolitical adversaries].”

Passage of the CHIPs and Science Act, which provides $52.7 billion for semiconductor R&D and manufacturing, was intended in part to reduce the nation’s reliance on foreign sources. But restructuring a major sector of the global economy “is not going to happen overnight,” Reed says. Major semiconductor producers have announced plans to build multiple fabrication sites in the U.S., but Reed says he would be “shocked if anything gets done in less than five years.” In the meantime, there’s always the possibility of a flareup between the U.S. and China, in which the latter cuts off access to essential raw materials or components for aerospace and defense production.

The promise of cheap production lured American manufacturers into relying too heavily on China for raw materials, Reed believes. But recent events like the war in Ukraine have prompted reconsideration of that strategy. “American has gotten pretty hip to the idea that you can’t just bank those discounts and assume there will be no long-term problems,” he says.

One short-term solution for U.S. manufacturers would be to increase the stockpiling of items needed for that purpose, in support of the long production and maintenance windows that typify the defense industry. But such materials would be of limited use in the development of modern-day hypersonic weapons, which are supported by the latest advances in artificial intelligence.

Hence the concerns of ETI over the condition of the present-day supply chain for hypersonic weapons development. The institute calls for more investment in the production and processing of high-temperature materials such as carbon fiber and titanium. At the same time, to address present and potential shortages in the workforce, it recommends tapping academia to equip students with “hands-on” experience in hypersonic technology.

Notwithstanding efforts to beef up domestic capability, continued ties to friendly foreign sources are essential, ETI says. It wants DOD to prioritize establishment of sourcing agreements with Australia and Canada to diversify critical raw-material supplies away from China.

Reed counters that the focus should be, to the greatest extent possible, on production in North America, even if that means absorbing some higher labor costs. In sourcing from Australia, he says, “you still have to transport those goods across an ocean.”

In ETI’s view, though, the first order of business is for DOD to provide industry with a consistent demand signal. “Companies must know that they will receive a return on investment,” the report says. “Industry is eager to invest in hypersonic technology, but the business case must exist for companies to invest in the necessary infrastructure and personnel.”

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.