Home » Moderna Finds That Creating a Covid Vaccine Was the Easy Part

Moderna Finds That Creating a Covid Vaccine Was the Easy Part

November 8, 2021

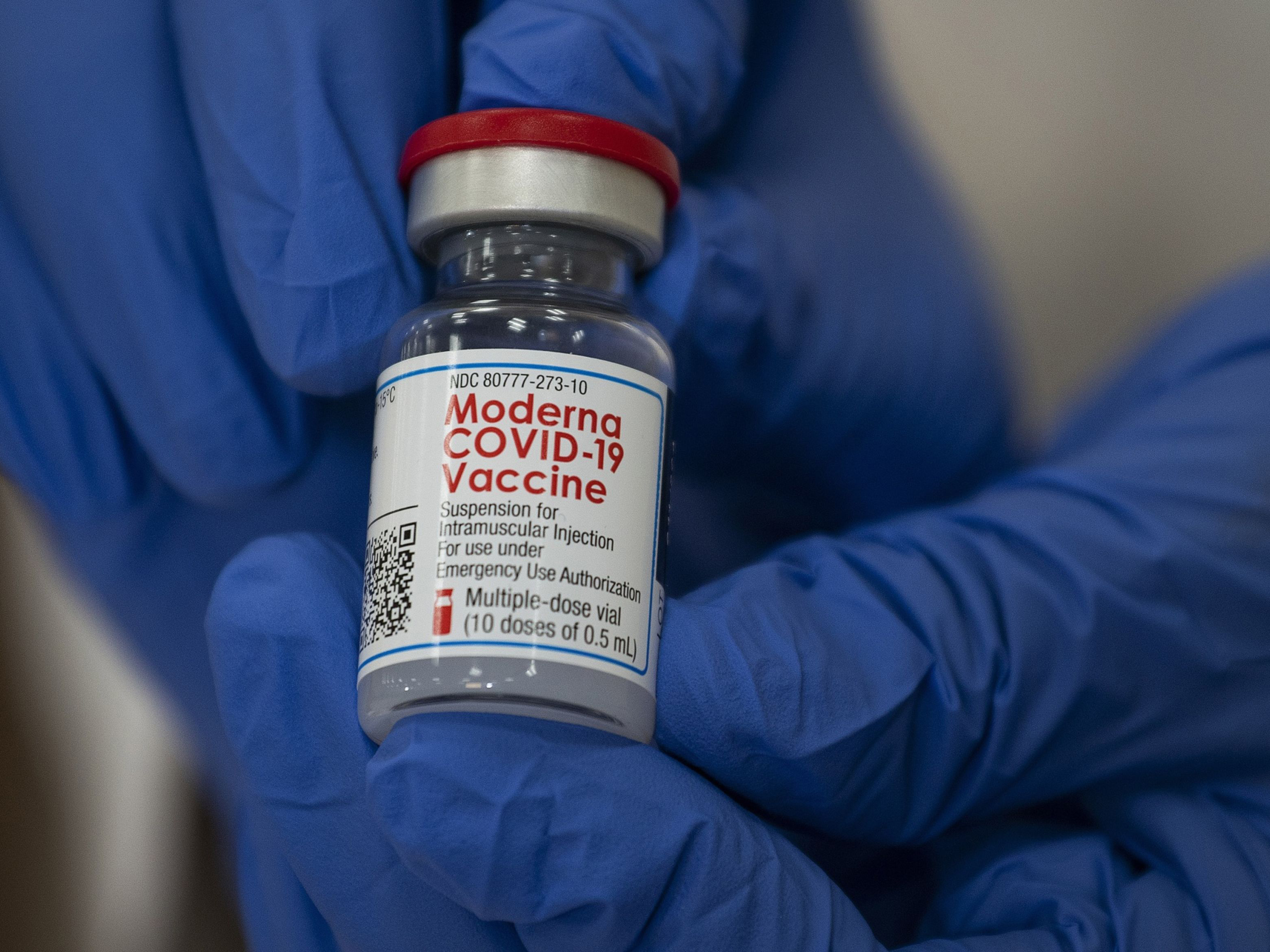

Moderna Inc. has some of the highest-flying science in the biotech business. It brought its messenger RNA vaccine to the market in less than a year, faster than almost anyone thought possible.

But more than 10 months after U.S. regulators first authorized its potent shot, Moderna is finding that inventing a COVID-19 vaccine was actually a relatively straightforward task compared with what would come next: ramping up vial-filling operations on multiple continents and distributing the vaccine to countries around the world in the middle of a devastating pandemic.

Moderna shares plummeted on Thursday after it announced it would be able to supply only 700 million to 800 million vaccine doses this year, down from its previous projection of 800 million to 1 billion doses. It attributed the lower forecast not to any complications in making the mRNA itself, an issue it dealt with earlier this year, but to delays in filling vials and delivering them in international markets.

That added to pressure on the stock that has been building for months. Since Aug. 9, Moderna has dropped 51%, wiping out almost $100 billion in market value.

In fact, the company says it already has produced more than 900 million doses of the bulk substance for its vaccine, which consists of messenger RNA coated in lipid nanoparticles. But it apparently won’t be able to get all those doses into vials and where they need to go before next year.

On a conference call with analysts last week, Chief Executive Officer Stephane Bancel tried to make the best of it, comparing the delays to “teething problems” as Moderna attempts to expand from a boutique biotech firm in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to a global vaccine distribution powerhouse.

Moderna, of course, isn’t the first vaccine maker to run into production delays. Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca Plc and Novavax Inc. — or their manufacturing partners — have all hit production snags that have slowed rollouts of their vaccines at some point during the past year.

Novavax CEO Stanley Erck said in an interview Friday that his company had no factories of its own at the outset of the pandemic, and had to create a network of internal and external production facilities from scratch. Among other problems it encountered were shortages of things like filters and 4,000-liter bags needed for producing its vaccine in insect cells.

“Seemingly simple things ran out of global supply,” Erck said. But now, he said, the problems are mostly solved and the company and its partners should be able to produce 200 million doses a month by early next year.

Pfizer Contrast

One company that has had fewer production problems this year is Moderna’s vaccine rival Pfizer Inc., which partners with BioNTech SE. Pfizer has already produced 2.6 billion doses and shipped 2 billion of them this year. Last week it raised its 2021 forecast for vaccine sales to $36 billion, with plans to produce 4 billion doses next year.

Unlike Moderna, giant companies like Pfizer have existing factories to turn to, long-term relationships with an extensive base of suppliers, as well as numerous supply chain experts to plan for every possible contingency when production runs into unexpected snags, said Julie Swann, a health systems expert at North Carolina State University. That gave Pfizer a big advantage over Moderna, Swann said.

Prior to the pandemic, Pfizer already had capacity to make 200 million vaccine doses a year, with 12 biologics and vaccine-manufacturing facilities in 10 countries. Moderna’s lone factory was a plant in Norwood, Massachusetts, that had never produced anything at large scale before Covid.

Bancel said Moderna didn’t have a single employee in Europe on its commercial team before the pandemic.

“It’s not surprising that if someone had a problem, it would be them,” said Swann.

Moderna has relied entirely on contract manufacturers to put its vaccine into vials, the process known as fill and finish. While that helps it produce more shots, it also creates a complex web the company needs to manage.

Procedures need to be precise when producing tightly regulated pharmaceutical products, meaning it can take time to develop them. At every factory, doses have to be meticulously tested for sterility and the correct dosages.

And then there are the complexities of shipping and distribution. In the U.S., where most of its doses went in the first half of the year, the federal government paid McKesson Corp., the country’s largest pharmaceutical distributor, to deliver Covid shots. That meant Moderna could focus primarily on making its vaccine.

Now, as it turns to international shipments, Moderna and its contractors have become major exporters of a highly regulated drug product. Those challenges will only grow as Moderna expands to poorer nations without well-developed infrastructure.

When delivering vaccines overseas, Moderna must coordinate clearing customs, providing certifications and signing off on deliveries, among other tasks, a spokeswoman said in an email to Bloomberg. Many of the doses are going to countries for the first time and the process needs time to smooth out, she said.

There’s a process to package, test and release vials before they’re shipped, all of which require more workers, she said. The company has hired more people to accelerate the process.

Moderna still expects to sell $15 billion to $18 billion worth of its shot this year and even more next year, making it one of the best-selling pharmaceutical products in the world.

“Pfizer just has extraordinary manufacturing built up all over the world, so the fact that Moderna has done as well as it is, it’s sort of like a David compared to the huge Goliath of Pfizer,” says Tim Springer, a Harvard scientist and an early Moderna investor who still holds shares. “It’s extraordinary.”

Kids Doses

Moderna’s lagging international supply chain isn’t its only recent setback. The company is falling further behind Pfizer in getting its Covid vaccine on the market for adolescents and children. There are concerns that its shot, which uses a higher mRNA dose than the Pfizer one, may have a slightly higher rate of rare heart inflammation side effects.

Moderna’s application for authorization of its vaccine in kids 12 to 17 has been at the Food and Drug Administration since June, and the agency may not complete its review of heart side effects in children until January, according to Moderna. Its own safety database shows no increased heart inflammation risk for its vaccine in children, Moderna said Thursday.

By contrast, Pfizer’s vaccine has been available for children 12 and up since May, and it received U.S. emergency clearance to sell a lower dose for kids 5 to 11 in October.

Going forward, antiviral pills could reduce demand for Covid vaccines among those who are vaccine-hesitant. Pfizer on Friday said it would seek U.S. clearance for its COVID-19 pill, after the five-day treatment dramatically slashed hospitalizations and deaths in a big trial of high risk patients. The revelation sent Moderna shares cratering almost 17%.

Springer sees enormous potential for Moderna’s pipeline, which includes a combination shot for flu and Covid, mRNA-based cancer vaccines and an mRNA treatment for cystic fibrosis patients who don’t benefit from current drugs.

Those efforts could take years to come to fruition. For now, Moderna faces investors searching for proof it can deliver more of its lone existing product.

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Related Directories

Subscribe to our Daily Newsletter!

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.

Popular Stories

2024 Supply Chain Management Resource Guide: There's Only One Way Off a Burning Platform

VIEW THE LATEST ISSUECase Studies

-

Recycled Tagging Fasteners: Small Changes Make a Big Impact

-

Enhancing High-Value Electronics Shipment Security with Tive's Real-Time Tracking

-

Moving Robots Site-to-Site

-

JLL Finds Perfect Warehouse Location, Leading to $15M Grant for Startup

-

Robots Speed Fulfillment to Help Apparel Company Scale for Growth