Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It’s the beginning of October, just the start of what the retail world simply calls “peak.” But the industry is already in various forms of panic that usually don’t take hold until the weeks before Christmas.

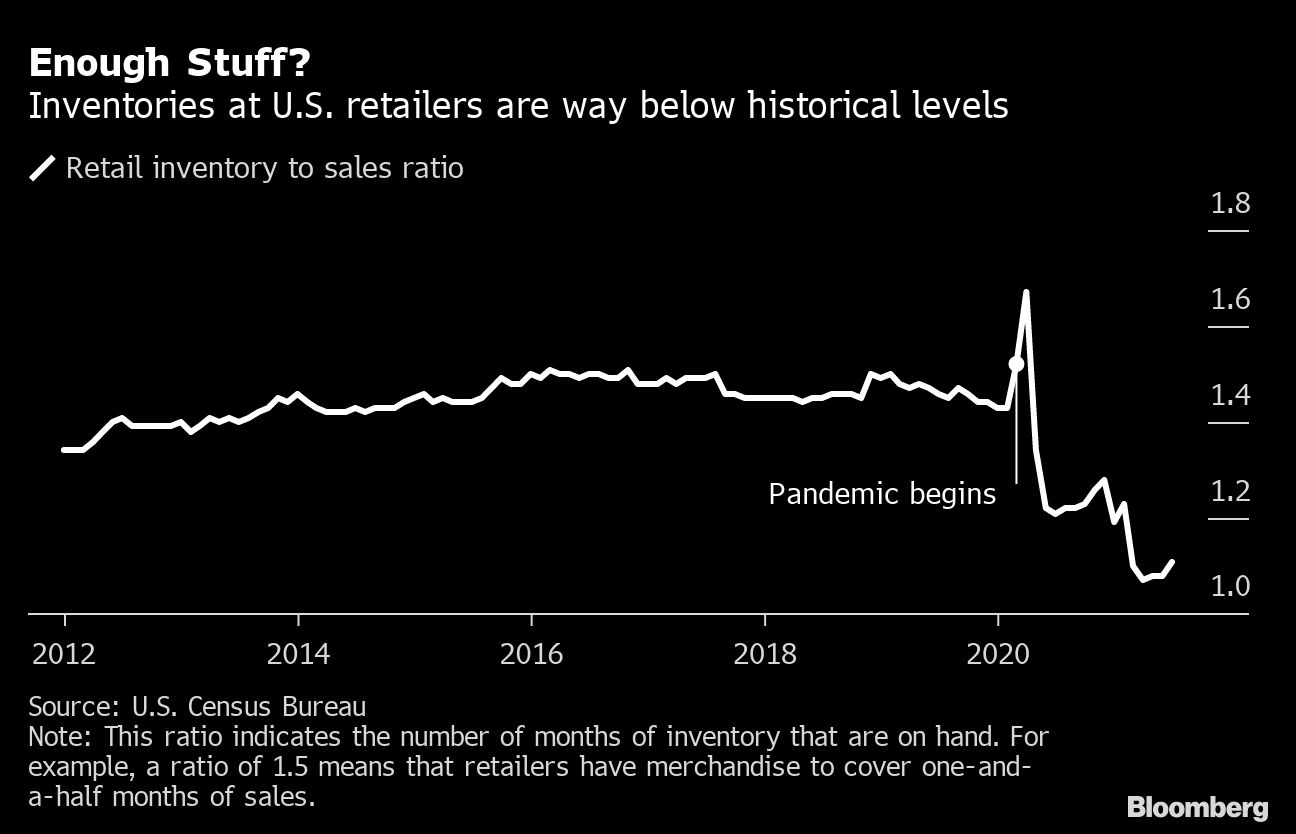

Early in the year, the hope was that the bottlenecks that gummed up the global supply chain in 2020 would be mostly cleared by now. They’ve actually only gotten worse — much worse — and evidence is mounting that the holiday season is at risk.

Across Europe, retailers such as apparel chain H&M can’t meet demand because of delivery delays. In the U.S., Nike cut its sales forecast after COVID-19 triggered factory closures in Vietnam that wiped out months of production. And Bed Bath & Beyond’s stock plunged amid shipping woes, with Chief Executive Officer Mark Tritton warning that disruptions would last well into next year. “There is pressure across the board, and you will hear about that from others.”

Covid outbreaks have idled port terminals. There still aren’t enough cargo containers, causing prices to spike 10-fold from a year ago. Labor shortages have stalled trucking and pushed U.S. job openings to all-time highs. And that was before UPS, Walmart and others embarked on hiring hundreds of thousands of seasonal workers to take on the peak of peak.

“I’ve been doing this for 43 years and never seen it this bad,” said Isaac Larian, founder and CEO of MGA Entertainment, one of the world’s largest toymakers. “Everything that can go wrong is going wrong at the same time.”

Now comes the rush of goods into the U.S. for Santa’s sleigh, which will only exacerbate all of this. It’s going to be a daunting holiday season — one that investors appear to be shrugging off despite analysts raising concerns that margins will likely take a hit. The S&P Retail Select Industry Index, which encompasses 108 U.S. companies including Amazon, Macy’s and Best Buy, is up about 40% this year and almost doubled since the start of 2020. Its combined market cap is $3.3 trillion, just a sliver below a record high from earlier this year.

That jubilance clashes with what’s happening behind the scenes. Retailers have resorted to buying goods made a couple years ago to make sure they at least secure some inventory, according to Steve Azarbad, co-founder and chief investment officer of the hedge fund Maglan Capital, which invests in retailers and distressed companies. In normal times, these items would be liquidated at closeout stores or in foreign markets, but not now.

“Retailers are having a really hard time filling their shelves,” Azarbad said. “I talk to a lot of suppliers, and they're telling me ‘I just can't fill all the orders I'm getting.’”

On the supplier side, Jay Foreman’s been making toys with manufacturing partners in China for more than three decades, and he’s never seen anything like this. His mid-sized toy company, Basic Fun, is on pace for its best year ever — possibly reaching $170 million in sales. There is no shortage of demand, with parents loading up on gifts as the pandemic drags on. But a dearth of cargo containers has left thousands of the company’s Lite Brites and TinkerToys waiting to be shipped. At just one factory in Shenzhen, there’s roughly $8 million worth of finished goods that could fill 140 containers.

“I got Tonka trucks in the south and Care Bears in the north,” Foreman, the company’s CEO, said of logistical troubles in China. “We’ll blow last year’s numbers away, but the problem is we don’t know if we’ll get the last four months of the year shipped. The supply chain is a disaster, and it’s only getting worse.”

MGA’s Larian is willing to pay more than $20,000 per shipping container — up from about $2,000 a year ago — and counts his blessings that he runs a private company that doesn’t have to answer to shareholders. He’s having trouble simply getting goods off cargo ships in the port of Los Angeles. MGA recently had more than 600 containers, filled with toys like its top-selling L.O.L. Surprise dolls, waiting to be unloaded for more than six weeks.

“There will be a shortage of toys this fall,” Larian said. “It’s going to be a tough year for retailers.”

When the pandemic knocked the global economy down in early 2020, factories slowed output or closed. Turns out, that was the easy part. Re-starting has been much more difficult. The supply chain has been choked by so many events, such as the Suez Canal blockage, and market dynamics like labor shortages and the spike in transportation costs that it feels like there’s been one “black swan” event after another, according to Lee Klaskow, a logistics analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence.

“The supply chain has never had the opportunity to get back to normal,” Klaskow said.

One of the better scenarios for the fourth quarter is that big retailers drastically increase spending on logistics — including resorting to using costlier air freight or chartering entire cargo ships — but still maintain their sales targets. That will likely mean they’ll see a hit to profit margins, but it could also lead to taking market share from smaller competitors who can’t match their deep pockets.

“We feel better than most that we'll get our product here for holiday," said Michael Mathias, chief financial officer for apparel chain American Eagle Outfitters. The retailer has spent more on air freight to secure goods for Christmas. “There will be some players out here who might not even get their product.”

Ken Hicks, chief executive officer of Academy Sports and Outdoors, is counting on that advantage to boost results. The chain, based in Katy, Texas, has been using its scale to prep for this peak season for months. That’s included importing goods sooner, moving shipments away from the overwhelmed west coast to ports like Galveston, Texas, and booking cargo capacity earlier in the year.

But even with all those mitigation efforts and the scale of a company that generated $4 billion in sales last fiscal year, Hicks said inventory levels were only “adequate.” There’s enough items to meet its sales goals, but he estimated the retailer is about 10% below where he’d like it to be. During the peak of the pandemic last year, the chain simply couldn’t source items like bicycles, exercise equipment and fishing rods. Now it can, just not as much as it wants. For example, each store would ideally have seven treadmills in stock, but it’s actually about half that, he said.

Making smart decisions on shipping and supply chain was enough for Janine Stichter, an analyst for Jeffries, to recently upgrade shoemaker Steve Madden to a “buy” after having a “hold” on it since starting coverage at the beginning of 2018. The company has shifted about half its production to Mexico and Brazil, reducing exposure to Asian markets, such as Vietnam. Making goods closer to the U.S. has made its lead times twice as fast as competitors, she said.

“Supply chain issues are getting continually worse,” Stichter said. For the rest of the year, “the key success factor will be the ability to supply product on time, or relatively on time.”

Meanwhile, Bank of America last week downgraded department-store chain Kohl’s from the equivalent of a buy rating to a sell and cut its target price on the shares by about a third because of mounting logistical costs.

The bigger, more systemic risk — one that could hurt every retailer — is that Americans spend less than expected because there isn’t enough inventory. The available goods may also not be all that enticing. The boom in shipping prices has forced manufacturers to make hard decisions about what to transport. Hicks, the Academy Sports CEO, predicted that shoppers “will have to settle more because they just won’t have as good of a selection.”

Shipping big items and goods with lower value don’t make as much economic sense right now. iPhones are small and pricey, making them an ideal good to ship or air freight amid spiking transport costs. But the same case can’t be made for low-end furniture or big stuffed animals. At Basic Fun in Boca Raton, Florida, Foreman is exporting a lot more Mash’ems because $135,000 worth of the small, squishy collectibles can fit on a single container. He’s moving far fewer Tonka trucks because they are bulky and take up more space, limiting the dollar value that can go in a container to just $36,000.

At Whom Home in Los Angeles, CEO Jon Bass said he had to remove about 70% of the company’s products — totaling thousands of items including wall decor and furniture — from the websites of retail partners such as Walmart and Wayfair because the company can’t source them. Or in some cases, surging costs for materials and transportation made an item pricier than a retailer was willing to pay.

“Consumers lose because their options are limited,” said Bass, who has been manufacturing goods for three decades. “It’s not a normal time in the business world. There is no stability.”

Rising costs in the supply chain, such as cotton prices hitting a 9-year high, and labor are also likely to boost what consumers pay, which could dampen spending. Or it might cause a bigger shift from hard goods to experiences and services — a trend already in place this year as Americans get back to traveling and eating out. The industry also expects much fewer promotions than usual because inventories are tight, which will turn off bargain hunters.

Add that consumer expectations are sky high, thanks to the ease and speed of e-commerce, and the retail industry is primed to severely disappoint the masses. If last holiday season was dubbed “shipageddon,” what will this year be called? It’s easy to see a boom in gift cards out of frustration as Americans tire of out-of-stocks and logistic mishaps.

“There is a certain amount of underappreciating for the risk” to the results of retailers, said Jennifer Bartashus, an analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence whose coverage includes mass merchants. “Supply chain affects everybody. Meeting customer expectations in an environment where everything is up in the air is nearly impossible.”

Some investors are wising up. Short interest in the SPDR S&P Retail exchange-traded fund, which mimics the S&P Retail Select Industry Index that’s surged this year, recently hit the highest level since late 2019.

But the retail industry has seen this coming. Large firms with the financial wherewithal have been storing goods in their own warehouses or renting space to make sure they can start filling shelves over the next few weeks. It’s another example of how “scale will be the pivotal differentiator” this holiday season, Bartashus said.

There’s also a push to get Americans to shop sooner for the holidays. One effort is trying to create a new shopping event in early October that will include retailers such as Guess? hosting livestream events on their websites. However, this seems like a gargantuan task considering e-commerce has trained the masses that purchases arrive in a few days like clockwork. Retailers have also traditionally saved some big promotions for the week before Christmas to drive a late spending push.

“Consumers might see news about port backups, but that won’t hit home until they try to buy the toy of the year and can't get it," Bartashus said. “That’s when they’ll hit crisis mode.”

Many retailers are already there.

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.